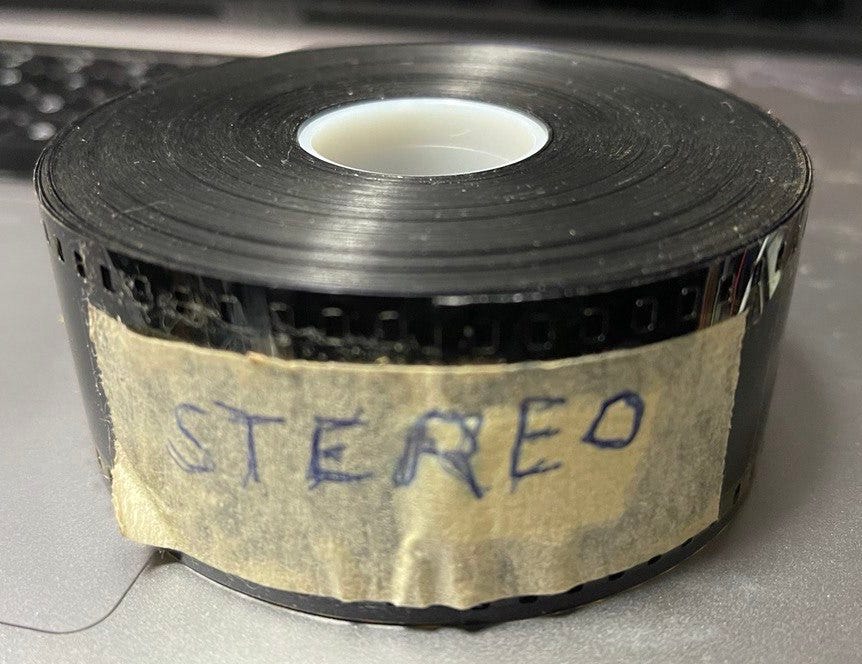

A while ago I decided to pick up some 35mm cinema film to help me experiment with projection optics. Old film trailers are by far the cheapest and easiest source of 35mm cinema film and can be picked up for a few dollars on eBay.

For those who, perhaps haven’t been to a cinema for a few years… these were short rolls of cinema film containing adverts spliced on to the beginning of feature.

In this case I acquired the trailer for mediocre 1997 disaster film volcano. The trailer I have seems more of less similar to this one.

While virtually all cinemas now use digital projection. Analogue film still holds a certain fascination. I suppose it’s just interesting to be able to see and interact with the storage medium itself. The image below shows the A in “A News Corporation Company”. You can clearly see the grain, and how this limits the optical resolution of the format:

Another curiosity of these late era analogue cinema films is that the audio is often encoded in up to 4 different analogue and digital formats. We can see how part of the frame has had some kind of data crammed into it:

The analogue soundtrack is used for legacy projectors with no digital decoder. The time code can also be used to sync the projection with external (often digital) sound sources.

But the SDDS (Sony) and Dolby digital both digitally encoded audio in a matrix like format on the film itself. This could then be decoded by an optical reader and decoder box. To me, this is pretty impressive for 90s technology. Each frame has 4 of these 78x78 matrices flying through the projector at 24 frames a second. That’s 96 matrices a second. You can now, 25 years later, pick up QR code readers that operate at ~60 scans/second, but I imagine it’s still “challenging”, particularly in real time.

I couldn’t find any public references to the dolby matrix encoding format. But this patent revealed some useful information. The matrices on the film shown above are 78x78 pixels, in the patent they suggest each matrix contains 5776 bits (38*19 bytes). This is in the same ballpark as the 6084 bits available in 78 square and subtracting out the fiducials we get 5684 bits. It’s possible that the approach evolved slightly from that show in the patent, but it seems like we’re in the right ballpark.

The patent suggest that data is stored in 8 bit bytes. Given that we have a data rate of ~584KB/s (Kilobytes/s) I suspect audio data is stored uncompressed. According to the patent, Reed-Solomon ECC also seems to be applied.

Using uncompressed data and applying error correction with Reed-Solomon probably helped simplify the electronics significantly. QR codes are relatively complex to decode, requiring the decoder to apply multiple masking patterns before the correct one is found.

In the dolby approach, the fiducials are likely used to keep the code correctly aligned to the sensor, and bytes directly encoded in matrix. The Reed-Solomon error correction then compensates for the (likely significant) damage and read out errors that occur.

Looking at the matrix itself, it certainly looks like single bytes are encoded in the X direction, we can often see identical blocks of 8 pixels adjacent in the Y-axis:

This suggests that the matrix should be relatively simple to decode. And it would be an interesting exercise to put together an image based dolby digital matrix decoder… so perhaps we’ll revisit this format again one day…

The evolution of film, and the different digital audio encoding methods proposed provides an interesting insight into a shared engineering journey based around the limitations of 35mm as the de facto standard. Now, almost completely abandoned and replaced by digital cinema… but at least analogue film still has some fans.

The alignment marks in the corners are a cross-multiplied Barker-code. This has a high enough correlation peak that pixel (fixel) centres can be located at around 0.1 feature size. The DD in the centre was included as a safety precaution – there were concerns that this would be a high-wear part of the film because of the shape of the sprocket-drive system. The original matrix was 76×76, not sure if it morphed to 78×78, possibly covered by the patents (which make interesting reading) including US Patent 5,757,465. I trust the statute of limitations is up on this one :) - Mark Atherton

SDDS occupies the space outside the sprocket holes on BOTH sides of the film. It also had more data as the speaker layout was left/left center/center/right center, right, surround left, surround-right, and subwoofer. There was also 'backup' tracks encoded- left+center, center, right+center and subwoofer. It was 12 total channels at about 2.2mbps ATRAC compression IIRC. An interesting side note, the two sides of the film were NOT synchronous(about 17 frames difference), so if a splice was made, it could read over the edit.

The timecode track was for DTS. It used an external CD data disc.

Also, Jelmer is correct- damage to the sprocket holes was not uncommon, and you could often hear the sound in the theater 'collapse' to standard Dolby Surround, due to damage on the film from poorly maintained projectors, or careless staff.